Thinking of Jesus, I climbed into the ferry at Fowey Town Quay, paid £2.50 to the captain, and set sail for the distant shores of Polruan which loomed out of green waters some 365 metres away.

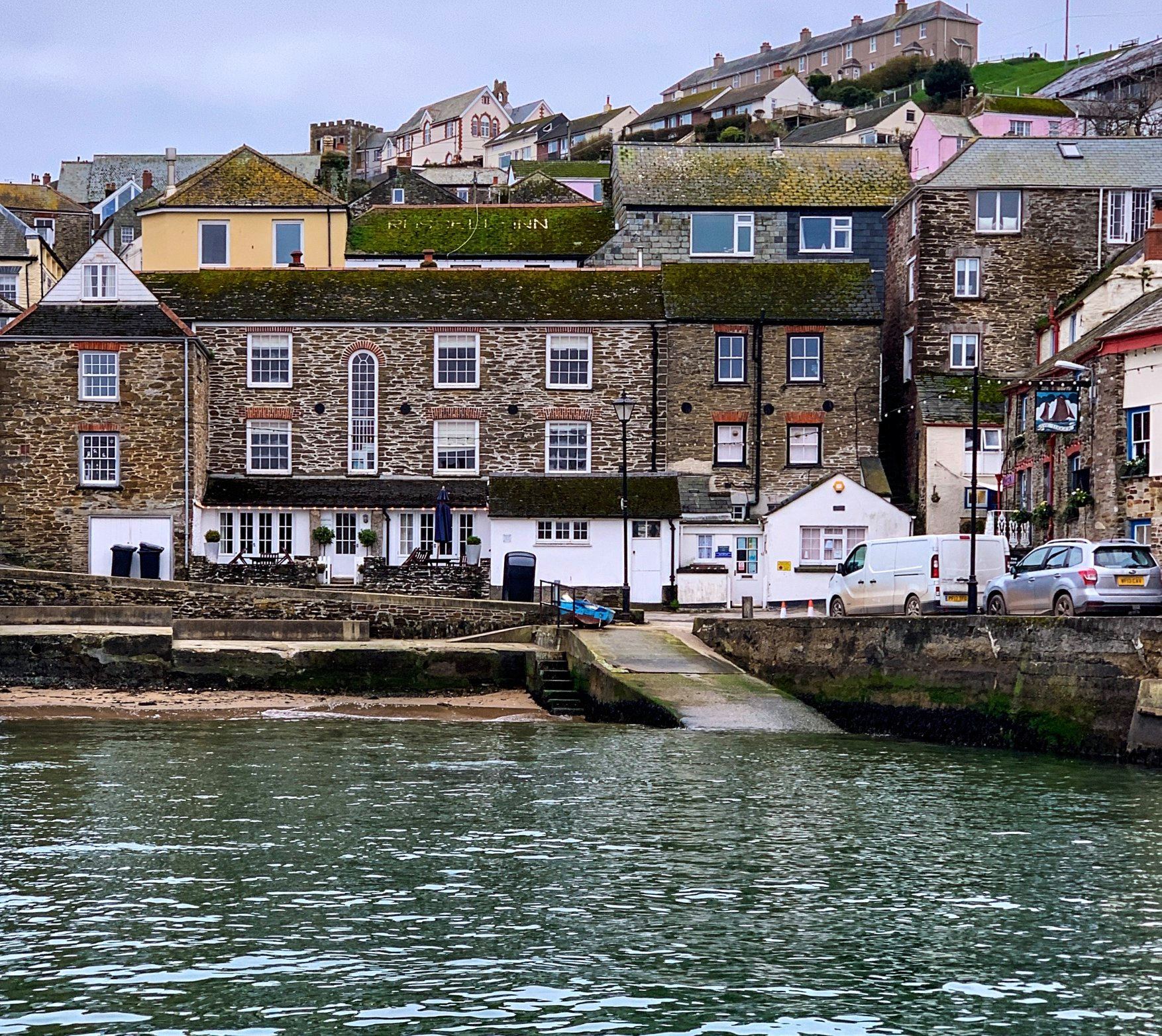

Polruan is water-bound on three sides, an ancient village clinging for dear life to a steep hill. How steep is this hill? Let’s just say that if some annoyed giant were to tilt the village a wee bit bay-side, most of its holiday cottages and the three or four people walking its narrow streets at any given point in the winter months would all tumble into very cold waters. Polruan lies in south-east Cornwall, four miles south of Bodinnick, across the short expanse of waters from Fowey that I was now crossing in a boat that belonged to C Toms & Son. The village has a biblical connection—if you are an imaginative believer, that is: once, a long time ago, a young Jesus is said to have come ashore here.

The possibility of Christ in Cornwall is predicated on what has come to be known as the ‘lost years of Jesus’. As the good Christians amongst us know, there is an eighteen-year-gap in our knowledge of his life, from the time he was twelve and vivaed elders at the Temple in Jerusalem on their knowledge of the scriptures, and when he returned to Nazareth at the age of thirty looking a bit like Mehdi Dehbi in Netflix’s Al-Masih. The gospels, usually good at reporting on his remarkable doings, including directly quoting him and his followers, is silent on these years. All we have from Luke (2: 41-2), for instance, is: “And Jesus increased in wisdom, in stature and in favour with God and men.”

Building on this, one thesis that historians and archeologists offer is that he put this time to good use, embarking on the very first Christian roadshow that the world has ever seen, ministering, prophesying, and perfecting the art of performing miracles—in short, building the foundations of his future church. Where exactly he went to do all this—whether he stuck to domestic travel in the Holy Land, or went international—is lost to history.

But that has not stopped folks from theorising and writing books on the subject. One theory that has exercised several writers including Islamic clerics is that he travelled to my side of the world. Twice. Once, during the missing years, to wander around the Sindh, Punjab and Ladakh regions; and the second time, after surviving his crucifixion, to die in peace in downtown Srinagar at the enviable age of one hundred and twenty.

Nicolas Notovich, a Russian blessed with rich imagination, wrote that Jesus spent time at the Hemis Monastery in Ladakh, as part of his plan to “improve and perfect himself in the divine understanding and to studying the laws of the great Buddha”. According to himself, Notovich was many things—a spy, a journalist, and an aristocrat. But one thing he was not was truthful. So perhaps it may not have surprised Notovich when, following his claim, which appeared in a French book titled La vie inconnue de Jesus Christ (Unknown Life of Jesus Christ), several others wrote several other books essentially calling him a big fat liar—among them, Bart D Ehrman (Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are) and Marcel Theroux (The Secret Books).

A second speculation is that Jesus came to Britain in the company of Joseph of Arimathea, his future disciple. Joseph was the wealthy merchant credited with burying Jesus’s body after the crucifixion. It is possible that Joseph of Arimathea took on Jesus’s guardianship; there is no mention of Jesus’s earthly father in the New Testament after he was twelve, and it is pretty much certain that Mary’s husband died around then. Joseph of Arimathea had mining interests in Cornwall. Tin was much sought after those days, and Cornwall had plenty of it, and Joseph, according to this legend, often visited.

Thus is it believed that once—or perhaps more than once—Joseph, with young Jesus in tow, walked into the ancient village of mariners that I was heading for.

When the ferry docked, I climbed out on to the Polruan quay. Except for a family of five—a couple, their two well-behaved kids and their equally well-behaved black-and-white dog—who were on the boat with me, there was no one around.

A shop named Wickle Picker, which also doubled as the village post office, showed light in one of its two large windows. To my left stood the boatyard that has sustained many livelihoods in the area, and built and serviced many ships over centuries. At one point, in the 1870s, the boatyard at Polruan was run by Jane Slade, “the only female shipbuilder in Cornwall”, who had inspired a 22-year-old Daphne du Maurier to write her first novel, The Loving Spirit. du Maurier (more on her later) is said to have invested in a boatyard around here herself, but the enterprise that I was looking at now belonged to C Toms & Son. On the main building, underlining the name of the proprietors, was scrawled in white lettering ‘1922’, ostensibly the year the business began.

Perhaps because I had come in search of the Son sent to earth by his Father, I could not help pondering over the historicity of C Toms and the achievements of his son. It is unlikely that the original C Toms (Connor, Christopher, Charles, Charlie?), if he had started out in 1922, would still be around. Had his son—the ‘&Son’ of the name-board—taken over? The unchanged business name suggested that the son’s name, too, was C Toms, and he, too, had one son who was his business partner. Was that true? Or was it just that the current owner was happy to live in his father’s—or grandfather’s—shadow? Perhaps he would claim his own identity, as years go by. You have to admit that even Jesus took his time to make his mark in the world.

Chastising myself for the vagaries of thought (it really is true that an idle mind is a devil’s workshop, isn’t it?), I made my way from the quay, passing the Luggers Inn, which showed signs of life, and the Polruan Surgery, which showed none. Fore Street is pretty much the high street of Polruan, and it ran perpendicular to the beachside, steep and narrow and hemmed in by buildings on both sides. My plan was to inspect Punche’s Cross, the place where Jesus had supposedly landed, which I had read lay near St Saviour’s Point. There was no one around to ask for directions, so I continued uphill, passing the Crumpet’s Cafe and Singing Kettle, both of which were shut.

I got lucky a little ahead, spotting a blonde woman hurrying out of her front door. She looked a lot like Raynor Winn, author of The Salt Path. Perhaps she *was* Raynor Winn. (Later research indicates that Winn may be based in Polruan.) She told me Punches Cross was inaccessible, so I asked for directions to the next best place, St Saviour’s Point. I was to take the School Lane, which I had passed, and go up to the carpark, “all the way up, as far as you can go”, and then walk down to the headland—from where I might, if I was lucky, be able to see Punches Cross. Maybe.

Obediently I backtracked and took the School Lane, which guided me up the St Saviour’s Hill. The carpark stood near the top, at the foot of the ruins of St Saviour’s Chapel. It occupied the site of the Boy’s School, which was destroyed in German bombing in WW2. More than the fact that the children there escaped without casualties in that incident, what makes the school—indeed the whole of Polruan—more colourful is another piece of associated history.

On 10th January 1922, owing to an intense dislike of their new headmaster, the free-spirited boys of the school went on strike, parading through the village with banners and flags. They also sang songs, some of them possibly rude. Police arrived to contain the kids. At which point, a horde of Polruan women—mothers and aunts of the protestors, I would wager—set upon the police. How I would have loved to see that sight of bobbies diving into the English Channel, chased by angry fisherwomen wielding makeshift clubs of pilchard! I would also have loved to report that the striking boys got what they wanted, but, alas, they did not. As it sometimes happens, some heads stay on longer than they should, and there is little that you and I can do about them except secretly pray for their humiliating and painful removal from office by way of syphilis, bubonic plague, or exposure to Piers Morgan’s breakfast monologues.

Interrupting the reverie of two hikers chilling on the hilltop, I had a quick look at St Saviour’s Chapel. There wasn’t much left of it to look at, actually, just one portion of a wall rising majestically, in a Stonehengeish way, from a wet carpet of grass. But the hilltop provided a good view of the St Saviour’s Point, from where I was hoping to see Jesus’s legendary port of entry.

The Christ in Cornwall thesis has several passionate proponents, among them one heavyweight English poet: William Blake. In fact, many of the arguments that situate Christ this side of the Channel draw from his work.

In the preface of Milton: a poem in 2 books, Blake writes:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green?

And was the Holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen?

Blake’s verses—never mind he wrote them some 1,800 years after the supposed visit and there was no earthly way he could have verified it—have been given much weightage by several writers over the years. Blake himself doesn’t seem terribly convinced about the incident, but theologian Dr Gordon Strachan takes great comfort in his words. The first chapter of Dr Strachan’s book exploring the possibility Blake poetised, titled Jesus the Master Builder: Druid Mysteries and the Dawn of Christianity, is, in turn, titled ‘And did those feet’. He went on to make a film as well, and called it—no surprises here—And Did Those Feet. In a BBC interview that followed up on the film, Dr Strachan said it was entirely plausible that Jesus was seen on England’s pleasant pastures (specifically in south-west England) arguing that a) the voyage involved was perfectly feasible, and b) Jesus had plenty of time to do it. “The Romans came here at the same time,” he pointed out, “and they found it quite easy.”

A more heartfelt argument is made by Reverend H A Lewis, as part of an anguished rebuttal to a 1939-published book, Glastonbury Truth and Fiction by Beatrice Hamilton Thompson. In his writing the reverend takes blanket umbrage at any and all attempts to disprove biblical incidents. Lamenting “the prejudiced attitude of the writer and her fellow sceptics”, he builds his argument along these lines: the legend of Christ walking the Cornish shores is part of the miners’ folklore in this area; the tin trade that facilitated Jesus’s visit(s) as per these legends did exist and indeed flourish with the Roman Empire; and there is not one word—the reverend is quite emphatic about this point—in the gospel narrative that disproves Christ travelled to Cornwall. Some folks may say the reverend is on shaky grounds here, but what his piece lacks in analytical rigour, the reverend makes up with passion.

Notable among others who support this thesis are Glyn S Lewis (Did Jesus Come to Britain?: An Investigation into the Traditions That Christ Visited Cornwall and Somerset) and Dennis Price (The Missing Years of Jesus: The Extraordinary Evidence That Jesus Visited the British Isles). Glyn Lewis, invoking the power of legends and citing Rev H A Lewis, builds the case, more or less, on the same foundations as the reverend. In a more detailed analysis, Price, committing the sin of imposed interpretation in his readings on a grand scale, begins with the ‘evidence’ of Blake’s verses and knits together latent meanings from various sources—the gospels, the foretelling of Christ’s coming he gleans in Virgil’s poetry, the ‘certainty’ that Stonehenge was “haunted at some point during its grim history”, and the legends about Jesus in Britain, including the popular Glastonbury tale—to make the rather circular claim that there is ”no doubt” the English poet knew about Jesus in Britain and hence “described” it “to perfection” in his verse. For £9.02, Price’s book makes for an expensive—but fascinating—reading.

A common thread, in all these writings, is that Jesus supped, on nights on end, with the miners of Cornwall and Somerset. According to Glyn Lewis, Christ, in the company of Joseph, is most likely to have sailed for England from the “Phoenician town of Tyre on the Mediterranean”, and once in the Channel, they came ashore—at least once—in Polruan, “at the eastern tip” of where River Fowey joins the sea, on a “colony of rocks”.

I was staring at that colony of rocks now, which comes into view as you walk downhill to St Saviour’s Point. In the distance, to my right, across where the river waters merged with the Channel, I could see the cottages of Readymoney Cove, white and mystical beneath a cloud of mid-morning mist, and beyond that, to the west, the green hills on the curving coastline that had once spurred the creative instincts of Daphne du Maurier (more on that later, folks). If I squinted, I could make out, on one of the bigger rocks in the middle, the Punche’s Cross. Legend has it that the white cross was left to mark the holiness of the site, though nobody really knows who left it, when exactly it was left, and how it was maintained (surely a wooden cross would not have survived these many centuries by the water). The first mention we have of the cross is in 1525, in the accounts of poet and historian John Leyland. Glyn Lewis speculates the cross was erected by the Phoenicians that Jesus sailed with and impressed on his voyage to England; that they returned, after his crucifixion, to honour his memory. Let’s just say that we know little about the cross. The only thing we can be sure is that it is now being maintained by the Fowey Harbour Commission, and Glyn Lewis has a fertile imagination.

I pottered around the headland for some time, clicking photographs and inspecting the rock formation from different angles, then decided to turn back. It was difficult to unravel one of Christianity’s greatest mysteries—seriously, where did Jesus go during his missing years?—when you were this cold and buffeted by wind. But before I left, I walked down to the edge of the headland, over uneven ground, as far as I dared, for another look.

Below, the green sea lapped around the rock formation, foaming at the edges. Punche’s Cross was completely cut off from the mainland. But I didn’t think that would have troubled Jesus much.

A version of this appeared in the Open magazine in February 2020.

Previous Next